Massalcoreig

Perhaps I'm more fortunate than many, in that I can locate the exact origin of one-half of my blood and DNA to a square kilometer of earth.

My parents married in 1953 in a small church in Barcelona; he was a US serviceman, and she was a trained hairdresser who worked as a governess. This union met with no small degree of skepticism from the Spanish half of the family, as there had been cases of US military men promising marital bliss in the United States in exchange for you-know-what.

I know very little about their courtship, except that once, during a paseo along the Ramblas in Barcelona one evening, my father made a sweeping gesture with upturned hand that was dive-bombed by pigeon excrement.

Apparently, in Spain, this is considered good luck.

My father’s intentions were, thankfully, honorable, and my mother was dutifully shipped to Brooklyn, New York, to begin a new life in a new culture. Three years later, their lives were graced with my arrival.

My early years were overwhelmingly Americanized. I was a nerdy kid with mostly nerdy friends, who collected rocks and butterflies, rooted for the Mets during their darkest times, and voraciously read any Batman comic and history book I could get my hands on. Spain was a mysterious land, only identified by the occasional, oddly light-weight, powder-blue airmail envelopes that would occasionally arrive in the mail, emblazoned with curiously old-fashioned-looking handwriting. I was yanked out of my insularity in the Spring of 1968 when I was told that my mother, brother, and I were going to spend the upcoming Summer in Spain. This was quite exciting, since no one in our neighborhood had ever traveled by an airliner.

This was the glorious ‘707 Era’ of air travel, where people wore their finest outfits when traveling; women wore gloves, and men wore suits and ties. Seven hours later, we were delivered to the Barcelona airport, which, in 1968, was, to say the least, different from JFK in New York City. I still can remember that first burst of hot air that greeted us as the hatch opened, as we descended a staircase to the tarmac, at which point I heard a loud cheer from the upper deck. It seemed as if the entire population of my mother’s hometown had come to greet us.

After being screened by very serious-looking men in absurd patent leather hats wielding submachine guns, we were hustled into a caravan of small, tiny little cars that belched black smoke and were driven to my mother’s ancestral village, Massalcoreig.

Massalcoreig is situated at the confluence of the Cinca and Segre rivers, near a Roman road known as el camí del Diable (the Devil’s Path), which connected Ilerda (modern Lleida) to Caesaraugusta (modern Zaragoza). It borders the province of Aragon, close to the small city of Fraga, which lies on the other side of the river, and was described in an early travel guide as being ‘a city renowned for its figs, and the thick-headedness of the inhabitants.’

The Cinca River was known as Cinga in Latin during the 1st century BC, a name given to it by Julius Caesar. There appears to be evidence that settlement in the area dates back to at least the Bronze Age. Caesar has a significant link to the area, as during the Roman civil wars, he defeated the army of Pompey’s two sons over a series of days where he consistently maneuvered his troops into positions where his opponents' forces could have easily been destroyed, but instead sent his troops in to fraternize with them. After several days, the entire opposing army changed sides and joined Caesar’s forces. This victory is renowned in military theory, as it is the only one on record where no lives were lost.

Later, under Moorish rule, it was known as Az-Zaytum, meaning ‘River of Olives.’ The name likely originates from an Arabic phrase referring to the resting place of the Quraysh, a famous Arab tribe. The Umayyads were a clan of the powerful Quraysh tribe of Mecca, and their rule in Spain lasted for several centuries. Relatives have told me that, to their recollection, the name is a corruption of the phrase ‘The Moor’s Rock’.

Massalcoreig’s position astride two rivers gave its soil great fertility, and the area is renowned for producing high-quality fruits, including figs, almonds, peaches, and pears. The resourcefulness of the farmers is reflected in a local saying that these people can ‘make bread from stones.’ Like most small rural towns, it hemorrhages young people to big cities such as Lleida and Barcelona.

This latter skill would come in handy during the tumultuous civil war (1936-39), where the town, a bastion of Catalan nationalism, found itself on the front lines of the northern theatre of operations, so well described in George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. In 1938, the front moved through the town. For a time, it was occupied by Spanish Nationalists and Italian troops, inherently hostile to the republicanism and anarcho-syndicalism endemic to the area.

My mother, a girl of perhaps 6 or 7 at the time, experienced war firsthand at this point, getting hit by a car chauffeuring an Italian captain. Horrified and having a daughter of his own about the same age, he drove her to a local field hospital, had her cuts and bruises dressed, and then took her home. A kind man, he befriended and was soon adopted by her family, often showing up unannounced with food. Some time afterwards, however, a soldier came by and dropped off his boots, saying that he had been killed. Before that, he had noticed that my grandfather’s shoes were in poor shape and had mentioned to his orderly that, if anything happened to him, they should be given to the family.

The dictator Franco was not kind to the area in the post-civil war era. I remember stories my mother told of being transported for hours to rice fields to plant rice, her only reward being the gift of a light blue béret of the fascist Falange to wear and a lunch of rice and beans.

This was the town I arrived at after a hot and dusty drive on a poor road that has since become one of the best superhighways in Europe. To say that culture shock awaited me is an understatement. The people spoke quickly and loudly, and everything smelled unpleasant. My first image upon entering the town was a small child munching on what looked to be a complete and anatomically correct chicken foot. Half of all bathrooms were outside, with piles of newsprint for cleanup.

I understand that these types of conditions are not uncommon, even to this day. I’m just trying to quantify the degree of recoil that my sheltered, privileged prior life had not prepared me for. I must, however, also testify to the incredible warmth and love that this heretofore unknown family began to shower upon my brother and me. Before long, I became fond of pan con tomate, various types of tortillas, and, of course, paella.

I was well looked after by all my relatives, particularly my mother’s younger brother, Tio Antonio, who took me to a bullfight —a rarity in Spain nowadays — and bought me Beatle records so I’d be a bit less homesick, and Tio Arturo, my mother’s first cousin, the Alcalde (mayor) who loved to play chess. We stayed at the home of my aunt, Nieves, and her husband, Tio Enrique.

Although Spaniards are typically swarthy (after all, it’s very sunny over there), Spain has a long history of Celtic inhabitation, leading to a comingling of genes into a phenotype known as the ‘Celt-Iberian.’ That’s why, especially if you head north, you see a surprisingly high number of red and strawberry blonde-headed Spaniards. Enrique was one of these. With hair color that was only matched by his face color, the result of a volcanic temper and hypertension.

Enrique was a master agriculturist. Once, when visiting with Martha’s parents, we had dinner with Enrique and Nieves in Massalcoreig. My father-in-law, no stranger to growing things himself, asked what, in the dinner we had just been served, was from their farm. Enrique’s face took on a look of surprise and beguilement.

His answer was typically laconic: ‘Everything.’

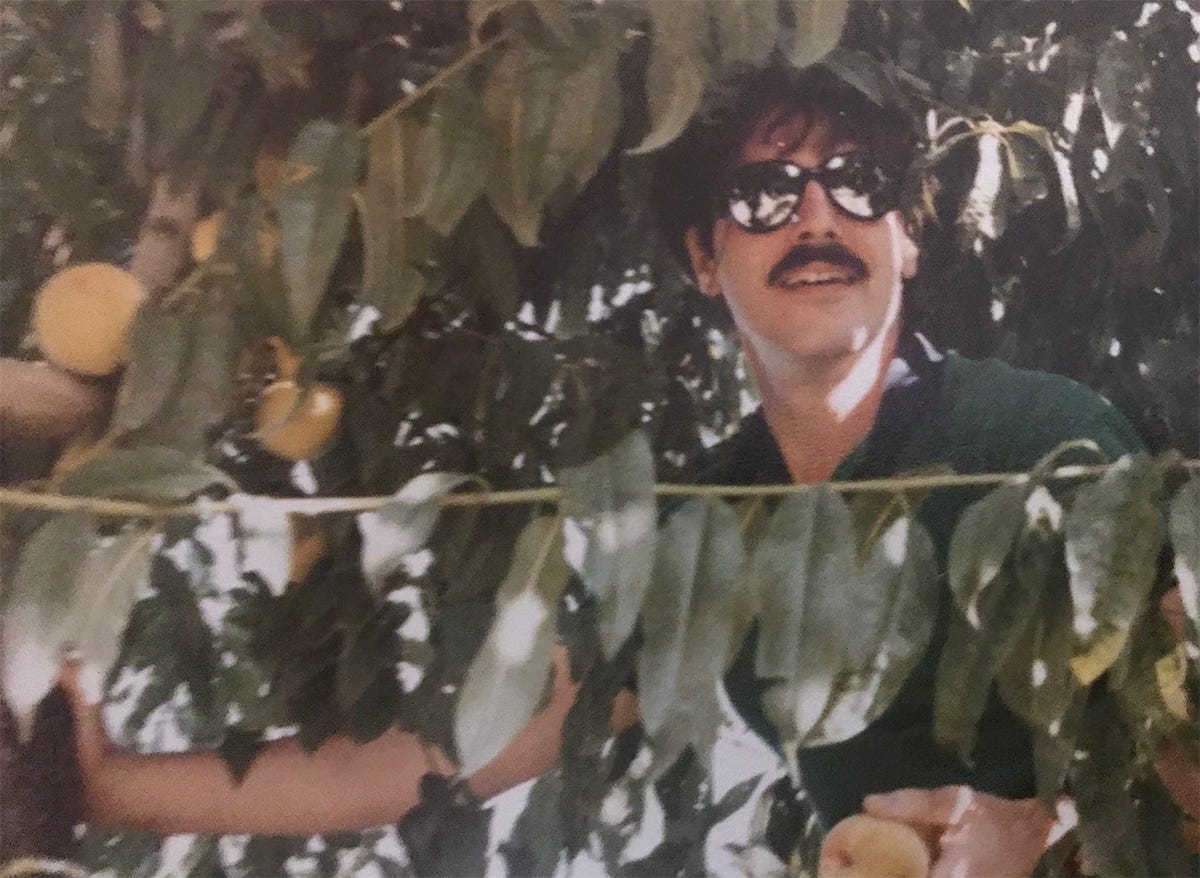

Enrique would take me out in the field with him. Lunch was typically a large fish (known locally as sardinas, but not our sardines) impaled on a branch arranged around a campfire, accompanied by bread with tomato, and a bit of cheese or a peach. He saw nothing wrong with a twelve-year-old aspirating a few gulps of red wine to wash it all down. Occasionally, we’d head out somewhere into the huerta, and he’d sweep away a clump of tree brush to reveal a Roman funerary stone or some other artifact.

Life changed dramatically with the death of Franco and Spain's transition into a constitutional monarchy. Entry into the European Union gave the farmers of Massalcoreig access to the Dutch and Belgian markets, which, from then on, bought their fruit directly from the vine. This changed lifestyles but not behaviors. People would still gather at the cafe and yell at the TV screen during football matches. Bathrooms were all inside now, and their terrible farm equipment was replaced by shiny John Deere equipment.

Through all this was my grandmother, Padrina. Her surnames were Vidal and Guardiola, which have some historical significance. Vidal is often a sign of a forced conversion from Judaism to Catholicism. In contrast, Guardiola identifies someone who worked as a guardian, caretaker, or watchman, and evidence from a 1601 municipal act suggests that at least one Guardiola was a card-carrying member of the Inquisition. The family must have been in the town for a very long time, as there are Guardiolas inscribed on the church wall with dates going back to the 1600s. My mitochondrial DNA group is T, which is not common in Europe but originates from the Levant and Caucasus regions of the Middle East. Therefore, I may have some Sephardic ancestry.

Sweet-natured and a very religious Catholic, she exuded contentment and happiness, despite years of abject suffering. My mother once told me that during the Civil War, she walked over twenty miles to a distant market town with a piece of furniture on her head to exchange it for a sack of potatoes.

Years of picking fruit had left her with contractures of the hand ligaments, and I suggested that she relocate to the U.S and stay with my mother while we tried different therapies. Surprisingly, she responded well to treatment.

Since the Brooklyn clinic where I practiced was only one block away from my mother’s house, I would often stop by for lunch. During lunch, one such afternoon, as I sat in a lounge chair with my head in my hands, she came in and asked me what the problem was.

Me: ‘I have a headache.’

Padrina: ‘What’s that?’

This woman had never experienced a headache in her entire life.

Peter, I read this while I was traveling with my family through small villages in the south of France, so it fit perfectly with the spirit of things. I'm so happy you are delving into your personal history. It's a good story!

Such an interesting genealogy and family history lesson. You come from remarkably courageous ancestors.