Returnings IV: Chaos/ Panic

Lung transplant trajectories are inevitably fraught with complications. That's just the way it is. Thankfully, with whatever I must encounter, I will certainly not be the first to experience it.

1.

The edge of chaos refers to the critical boundary between order and chaos, where complex adaptive systems (like us) have tuned themselves to the point of maximum capability. It is the region where a system is neither fully predictable (ordered) nor completely random (chaotic)—a sweet spot where there’s enough stability to maintain structure, but enough flexibility to allow adaptation and innovation.

The major concern in early-stage lung transplantation is ‘acute rejection.’ The most common form is acute cellular rejection (ACR), which occurs within the first week to first year, most commonly within 3–6 months. ACR affects 28–53% of recipients in the first year. High-dose corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) are the first line, often administered at home for milder cases. Despite its rather unsettling name, transplant teams don’t bat an eye at acute rejection. Or, as one of my case management nurses put it, ‘Just a fact of life.’

Up until recently, serial bronchoscopy with biopsy was the gold standard in rejection surveillance. But transbronchial biopsies are invasive and carry risks of complications up to 25.7%. Recently, a new blood test (‘Allosure’) has been used to help determine if rejection is active or imminent. It does this by measuring cell-free DNA, fragmented DNA originating from cells, and continuously released into the bloodstream. It then uses single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to distinguish between donor and recipient DNA. Elevated levels of donor cell-free DNA can indicate allograft injury, including rejection, and can be used to guide treatment decisions.

2.

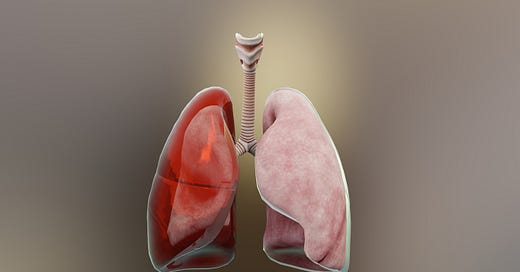

Although rejection was my worry as the Uber car sped us to Brigham, it turns out I had developed something much less common, and in the short term, likely more dangerous.

Called a hemopneumothorax (literally Latin for ‘blood and air in your chest’)—it meant that the space between the chest wall was filling up with blood and air. However, even arriving at this diagnosis had to pass through several early working diagnoses, including empyema (infection). The infection riddle was doubly baffling because, while I did have a skyrocketing white blood (neutrophil) count, there seemed to be no evidence of infectious organisms, despite numerous cultures.

There are several treatment approaches to hemopneumothorax, and I was first subjected to a protocol that attempted to drain the area with repeated needle insertions through the back wall in a widening circular pattern. This did not work.

Then the team opted for the most common treatment, which was to reinsert a new drain and try to get out as much as possible, trusting that the body would finish the job. Now, getting a chest drain inserted while under general anesthesia is a very different experience that getting one with a simple topical anesthetic, and this drain had to be inserted into a site that virtually guaranteed that for the entire length of time I would be host to it, deep, raw pain would be my constant companion.

Soon after, the pain management team stopped by and convinced me to have another nerve block put in to help control things. This was again, yet another very painful procedure, which had the added unfortunate result of being completely ineffectual.

So there I was, back in the hospital, day after day, for 28 days.

A bit of personal history: before this whole lung thing, I had never been in a hospital overnight.

Over time, you begin to develop what is called ‘hospital psychosis.’ This can be quite serious, with confusion, delirium, and other cognitive problems. I didn’t have these, but as I began to improve and tried to get back up on my feet, I began to notice that I would hyperventilate when I changed posture. I also have significant variations in my heart rate, from very rapid (tachycardia) to very slow (bradycardia), which was causing concern.

Some of my hyperventilation appeared to be due to the body not being able to fine-tune how it manages carbon dioxide (CO₂), the gas we breathe out. If CO₂ gets too low, it can stimulate a need to hyperventilate, and hyperventilation can cause CO₂ to go too low. The mind plays a big role in this as well, as anxiety pushes the feedback loop forward, and everything starts all over again. Rapid breathing expels CO₂ faster than the body produces it, leading to hypocapnia (low CO₂ levels in the blood). This causes the blood pH to become too alkaline due to the reduced CO₂, which normally forms carbonic acid in blood. That's why anxious people are sometimes told to breathe into a paper bag: you’re rebreathing the CO₂ in the bag, and that gets the level back up.

Although I am not an anxious person by nature, I will admit to a percentage of anxiety that would appear to stem from the current circumstances. For this, I was offered several antidepressants and axiolytics, but they just seemed to me to take too long to work, and I might as well try to figure this out myself. One clue I soon discovered was that none of this occurred while I was talking. This said two things to me. First, while using my vocalization nerves and muscles, my breathing was sent back to my autonomic nervous system for administration, which almost always runs things way better. Second, that the symptoms occur when getting up or sitting down seemed to have a lot to do with my very low blood pressure.

Finally, there was the unanswered question: How did this hemopneumothorax happen? I had my suspicions: principally that the week spent in isolation with Rhinovirus I received three heparin injections daily, coupled with the Plavix I had to continue to take due to the aforementioned stent, plus the continued post-transplant heparin injection, just made my blood so thin it just oozed into the space between the chest wall and lungs. The air part is easier. When a new lung is inserted into the chest of the recipient, it needs to fill the space. This adaptation can take time and initially results in atelectasis, a condition where part of the lung fails to inflate. When this occurs in non-transfused lungs, this is often called ‘a collapsed lung.’

3.

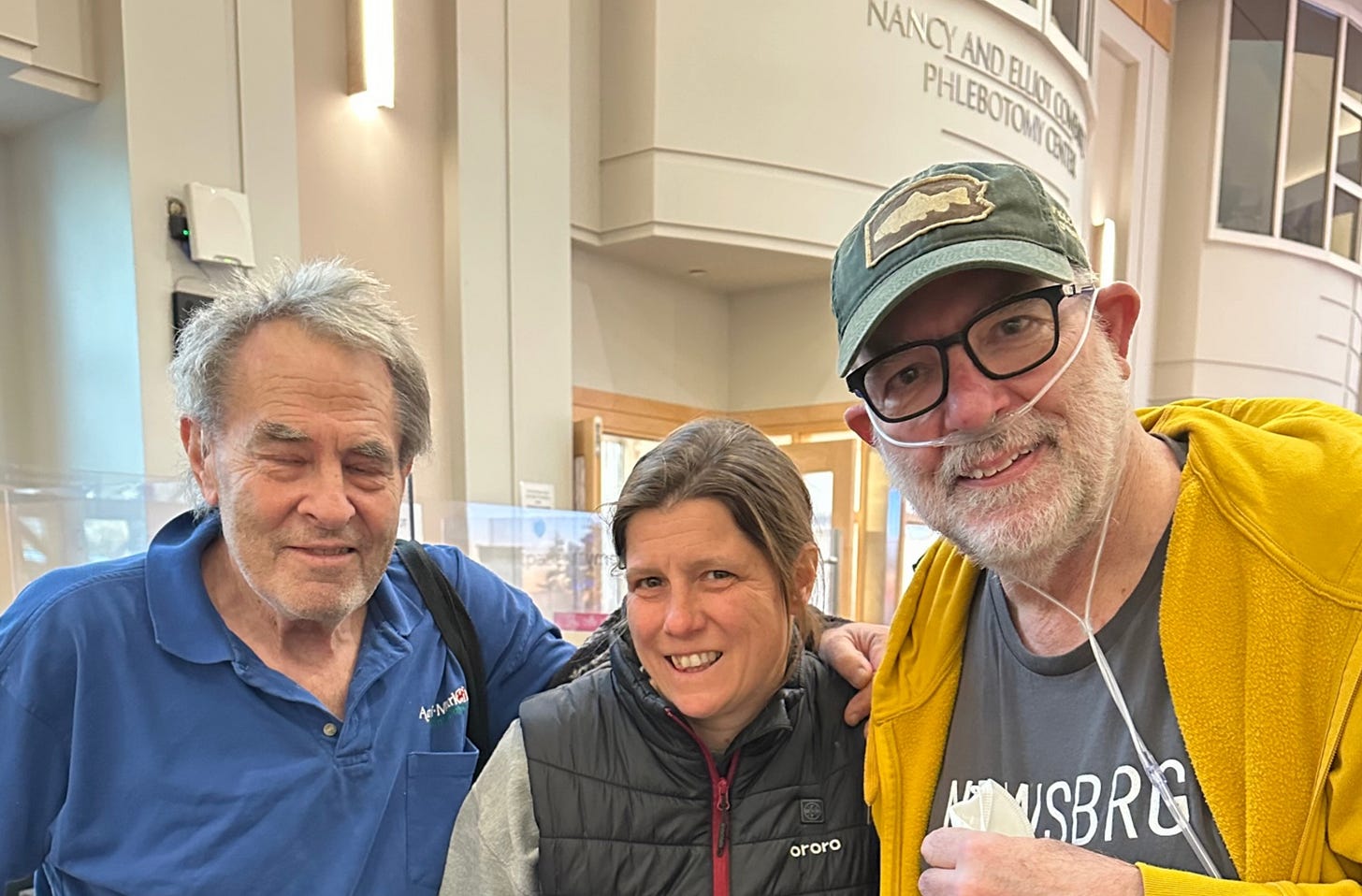

Early on in the transplant process, when I was still in the evaluation phase, I was in the Brigham phlebotomy pavilion for one of the innumerable blood draws that are part of the process. While waiting in the queue, I got to talking with a curmudgeonly gentleman who was there with his daughter for testing. Turns out this wonderful man was a lung transplant recipient, now over eleven years post-transplant. A life-long dairy farmer in Western Massachusetts, he soon became a mentor and touchstone for my current experiential parsings. Not a week goes by without a check-in call from John, and so often, my predicaments merely serve to jar a distant memory of a similar challenge from his earlier days.

As the days of my second stay at Brigham wound down, it was soon time for the ceremonial yanking of the drain (HUMM), a pharmacy protocol restructuring, and soon enough, Martha and I were back in the rental apartment. After a few days, we decided (with team approval) to head back to Connecticut so I could spend a few days at home. Dex, our Shih Tzu pup, who had been staying with his aunt Dorothy and cousin Quinn, came down for a few days. It had been a while since we had seen each other, and he was confused about who I was. However, since I am the only one in the family who calls him ‘Bubba,’ he only had to hear that to recognize me.

Next:

Returnings V: Just Keep Going.

Being an acute patient and a medical detective at the same time is quite a stretch. It's a revelation that the terrifyingly named acute cellular rejection is a "common" condition for these folks. Doesn't exactly reduce the freak out potential when it's you--I'm projecting. But one more barrier crossed. So happy you're back home.

What a journey you have had…awesome…take good care…