When Progress Sparks Protest

Two diners complain to each other about their shared dinner. The first complains that the food tastes terrible. The second that the portions are small. Welcome to the Tocqueville Effect.

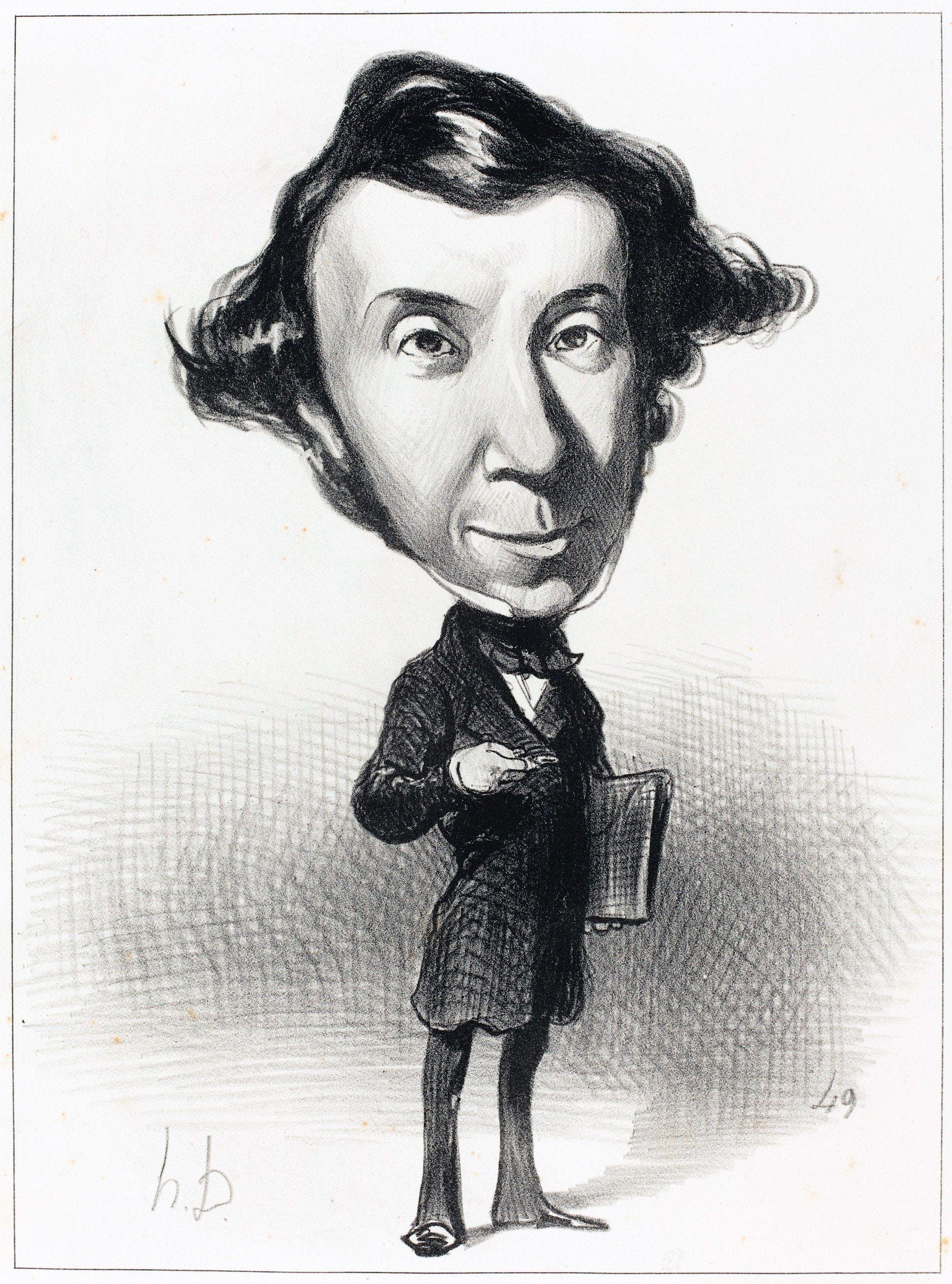

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (1805–1859) was a French political thinker, historian, and aristocrat best known for his book Democracy in America (1835–1840). His work explored how democratic systems shape society, highlighting both their strengths (like equality) and risks (like majority tyranny). A lifelong hypochondriac, he got it right at the end, dying of tuberculosis at 53.

He is the father of the ‘Tocqueville Effect,’ a concept that describes the curious phenomenon by which people become more frustrated as problems are resolved and situations improve.

In other words, as life gets better, an increasing number of people think it's getting worse.

A simple example would be in a town where the crime rate has dropped so low that the police start jailing jaywalkers because it‘s currently the most egregious crime. With too few assaults, more mild crimes might start getting treated like assaults, even if they shouldn't.

Here’s another: College access in the U.S. has skyrocketed since the 1980s, with more people earning degrees than ever. But soaring tuition and stagnant wages mean grads often drown in debt without the dream job they expected. This gap—more education but less payoff—fuels protests and demands for debt release.

As problems get smaller, the attention given to them must grow. If you shift the prevalence of something, people start identifying marginal things as being more significant. Oodles of stuff in our daily lives are under The Effect: literacy rates, blood lead levels, even ‘The Arab Spring.’ King Louie XVI might have kept his head a bit longer by not easing some feudal taxes and granting more legal rights, which raised hopes among the middle and lower classes, who, before this, just survived, accepting their lot because alternatives seemed impossible.

The idea of an "inverse corollary" to the Tocqueville Effect—where people settle or become passive when faced with limited choices is also accurate. We might call this ‘The Resignation Effect’ —when things are uniformly bad, we tend to look on the bright side of the situation.

Here’s an example: you go to a supermarket to buy some fruit. Of course, when you go to pick your fruits, you want only the freshest stuff. But if what's on display is a little less fresh than ideal, you might consider a speckled banana or a squishier grape OK.

A lack of choice or hope breeds complacency. People don’t fight because they can’t imagine better. It’s the flip side of the Tocqueville Effect, where a taste of progress lights a fire, and why the best totalitarian regimes strive for a bare existence level in the populations they rule.

Steven Pinker’s work, especially in books like The Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now, argues that humanity has made massive progress over time—less violence, better health, more wealth, and greater rights for most people. This progress can paradoxically fuel unrest, as people’s expectations rise faster than reality can keep up. For example, Pinker might point out that global poverty has plummeted since the 1800s, and literacy rates are near-universal in many places. But the Tocqueville Effect suggests that these improvements can make remaining inequalities—like wealth gaps or systemic biases—feel more glaring.

People today, especially younger generations, might feel frustrated because they’re told the world’s better, yet they still face issues like climate change, unaffordable housing, or social injustices. Pinker acknowledges this tension, but argues it’s part of the growing pains of progress: as life gets better, people demand even better, which can drive further change.

Very nice. A new way of looking at the struggles.